US tariffs threaten the Malaysian economy beyond the simple reduction of trade, placing the crucial solar panel and semiconductor industries on a careful balance. Western and Chinese firms comprise a significant amount of Malaysia’s production capacity in these sectors, but the tariffs are pressuring many to leave. To maintain its economic capability, Malaysia has been forced into an awkward diplomatic balancing act between the US and China, warming up to Chinese advances while conceding to US trade demands.

In January 2025, Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim spoke at the London School of Economics. In his address, he discussed the importance of good policy to enhance global welfare, saying “the imperative of responsible governance enjoins us to…take decisive action for the greater good, namely, sustainable economic growth, and shared prosperity.”

But as the clock turned on April 2nd, Malaysia woke up to the fact that “responsible” governance means something different to the world’s powerful. As the United States engages in its unilateral tariff hikes, Malaysia will find that it will lose not only international trade, but the countless jobs, factories, and investments foreign firms have brought, especially in capital-intensive solar panels and semiconductor industries. Recent news has seen Malaysia negotiate with the Americans, conceding on many of their demands, and warming to Chinese overtures. But no matter how awkward the balancing act, it may be necessary to keep these two industries, and by extension the Malaysian economy, strong.

A Cosmopolitan Malaysia

April 2025 was not the first time Asia had seen an episode of American tariffs. During the first Trump Administration, the U.S. imposed tariffs on hundreds of billions of dollars’ worth of Chinese goods. These tariffs, alongside rising wage costs and a tight manufacturing labour market, pushed many Chinese producers to consider offshoring to Southeast Asian countries, attracted by low labour and material costs.

Beginning with basic consumer goods, such as apparel and footwear, foreign manufacturers have since expanded into highly capital-intensive goods, such as solar panels and semiconductor chips. Chinese firms account for 80% of Malaysia’s solar manufacturing capacity, according to Wood Mackenzie, an energy analytics firm. In the Malaysian region of Penang, InvestPenang—a government-run foreign investment lobbyist—the number of Chinese firms jumped to 55, mainly in semiconductor manufacturing, compared to 16 pre-2018 tariffs.

Western firms also play a large role in Malaysia’s cosmopolitan manufacturing scene. In the semiconductor industry, named a “national priority” in 2024, large Western multinationals, such as Intel, AMD, Renesas, Infineon, and Micron, play a substantial role in the creation and rapid expansion of Malaysia’s production capabilities. In just last 5 years, Intel committed $7 billion USD for a new 3D chip plant in 2021, German firm Infineron pledged €5 billion ($5.4 billion USD) in 2022, Nvidia has been working on a $4.3 billion AI data center, and Texas instruments prepared plans for a 2024 expansion worth ~15 billion RM combined (or about $3.5 billion USD).

The Tariffs

Malaysia clearly relies heavily on foreign firms in the solar panel and semiconductor industries, but that presents a potential problem. The Financial Times pointed out the failure to create a domestic equivalent to large multinational companies in the semiconductor industry, highlighting that domestic firms make up little of its production capacity. The high foreign ownership of solar panel production suggests it’s a similar phenomenon there. That common issue of foreign over-reliance introduces a key vulnerability that some foreign actors may, whether purposefully or not, exploit.

As early as 2024, U.S. manufacturers alleged that Malaysian producers benefited from Chinese subsidies and unfair pricing practices, leading to a 9% levy on Malaysian solar panel imports that October. That leads into April of 2025, when, citing the same reason, the U.S. placed 24% blanket tariffs on most Malaysian exports. Given the concentration of foreign firms and emphasis placed on export markets, these foreign-made policies are having an outsized impact on the solar panel and semiconductor industries.

In the solar panel space, large foreign producers, such as Jinko Solar Co. and Risen Energy, have halted planned expansion projects and reduced operations in light of the tariffs. The Malaysian Photovoltaic Industry Association, representing solar panel producers, suggested that more Chinese companies are expected to withdraw, given that many only set up shop to target the U.S. market. These closures put at risk thousands of jobs and threaten the whole industry.

Even in the semiconductor space, exempted from U.S. tariffs, firms are feeling the pinch. Smaller and medium-sized enterprises have been hesitant to invest amidst the uncertainty, while big multinationals, such as Intel and AMD, face increasing pressure to reduce international operations and reshore to the U.S. As semiconductors make up almost $13 billion USD in export volume and was Malaysia’s 6th largest export product in 2023, these developments should cause worry. The Trade Minister, Tengku Zafrul, has already admitted Malaysia will likely miss its 4.5-5.5% GDP growth target this year owing to “uncertainties stemming from the U.S. tariff policy.” Even as the U.S. temporarily pauses tariffs until July, that potential for decline still looms large.

A Balancing Act

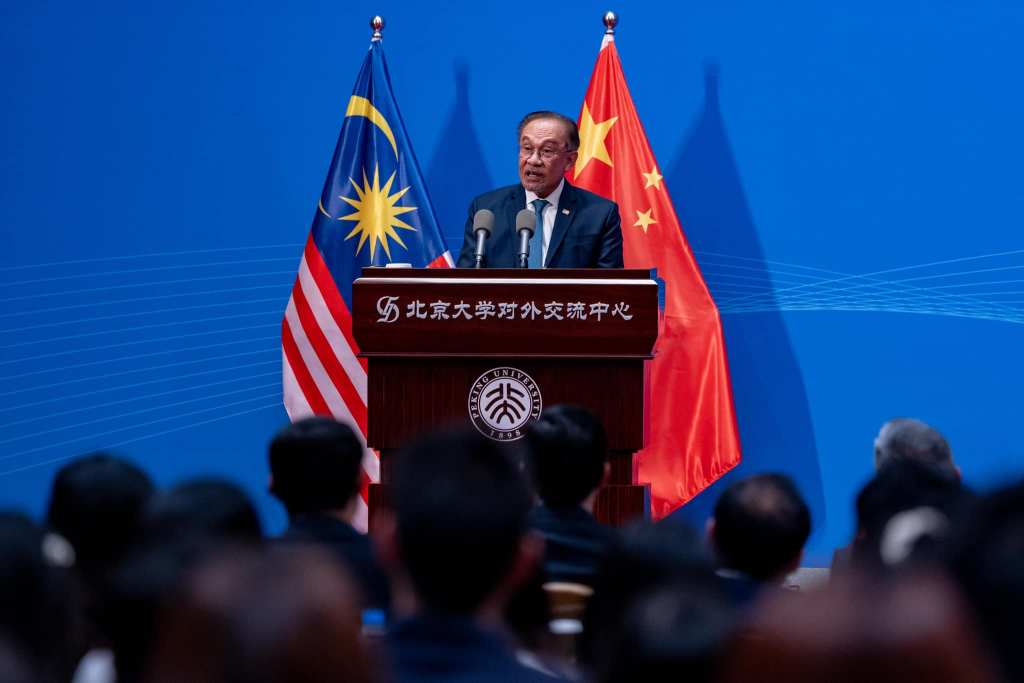

Less than two weeks after the U.S. tariffs were announced, Malaysia hosted Chinese President Xi Jinping in what many see as an overture for Malaysia. Incorporating both Malay and Mandarin proverbs into his speech at a state banquet, Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim arguably signaled a broader inclination to pivot toward China—a partner perceived as more reliable and steadfast than Trump’s America. At the same time, Malaysia has signalled it is willing to budge on key trade concessions to the U.S., such as non-tariff trade barriers and stricter semiconductor controls, capitulating to allegations of unfair trade practices and collusion with China.

Now, Malaysia’s high-tech industries are stuck between a rock and a hard place, highly sensitive to the potential impacts of a withdrawal of foreign capital. Malaysia may have no choice but to play the balancing game. Malaysia’s manufacturing base was built when the world agreed on shared economic prosperity. But as much as they wish it would stay, the world has moved on.

Image credits: Facebook page of Anwar Ibrahim

Jackie Wang

Jackie is a Bachelor of Arts student studying Public Policy and Economics at the University of Toronto. Having immigrated from China, Wang has engaged with both sides of the pacific, giving him a particular interest in Chinese political, cultural, and economic affairs.