The global race for artificial intelligence is usually framed as a battle over chips, code, and national security. But behind the scenes, the AI economy runs on something far more basic: water. From cooling data centers to manufacturing semiconductors, modern computing depends on enormous and growing volumes of freshwater. As climate change strains water supplies in many of today’s tech hubs, this hidden constraint is beginning to reshape where AI can realistically be built and sustained. In the years ahead, access to reliable water may matter as much for digital power as access to advanced technology itself.

The history of industrial power is often the history of geography. The rise of the British Empire was underwritten by the proximity of coal seams to navigable waterways. The American Century was fueled by the vast oil reserves of Texas and California. In Washington today, however, the assessment of the next great industrial revolution, the race for artificial intelligence, has become detached from this material reality. Policymakers focus on the export of semiconductors and the security of code, treating the “cloud” as an ethereal realm that exists independent of the physical world. This is a strategic error. The digital economy is physically extractive, and its most critical constraint in the coming decade will not be silicon, but water.

As the computational intensity of the global economy accelerates, the map of great power competition is being redrawn by hydrology. The “sovereign AI” ambitions of nations from the Persian Gulf to the South China Sea will soon collide with the hard limits of their aquifers, which are underground layers of rock and sediment that store and supply freshwater. In many arid regions, these reserves are being depleted faster than they can naturally recharge, creating a fixed ceiling on how much water industry, cities, and data centers can sustainably draw. This divergence creates a new form of structural power. In the mid-twenty-first century, water-rich nations will not merely be environmental sanctuaries. They will be the necessary landlords of the global intelligence infrastructure.

The Thermodynamics of Intelligence

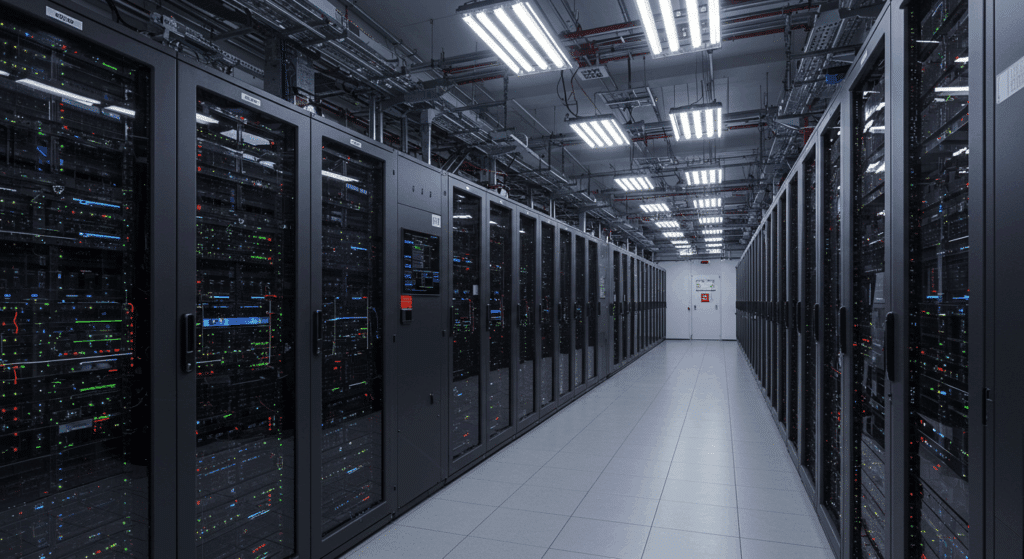

To understand the strategic threat, one must look past the software to the industrial reality of the data center. Training a frontier AI model is a thermodynamic event of industrial scale. As clusters of graphics processing units (GPUs) execute the billions of calculations required for modern deep learning, they generate immense heat. Dissipating this heat requires cooling infrastructure that is colloquially described as “thirsty.” While air cooling is possible, high-performance computing increasingly relies on liquid cooling or massive evaporative towers to maintain efficiency.

The quantitative dimensions of this challenge are distinct. Academic research indicates that training a single large language model such as GPT-3 can consume roughly 700,000 liters of freshwater, a figure that excludes the water consumed in generating the electricity to power the facility. When expanded to the “inference” phase, where models are queried by millions of users daily, the consumption scales exponentially. Goldman Sachs Research estimates that AI will drive a 200 terawatt-hour increase in power demand by 2030, a shift that carries a massive, often uncounted hydrologic price tag.

This thermodynamic reality forces a trade-off. Operators can choose “air-cooled” systems that consume zero water but require significantly more electricity to run fans, or “evaporative” systems that are energy-efficient but consume millions of gallons of water annually. In a world where both grid capacity and water tables are stressed, there are no free lunches. Already, the strain is visible. In its latest environmental report, Google revealed that its data centers consumed over 6 billion liters of water in a single year, a sharp increase driven largely by AI workloads.

The Hydro-Political Supply Chain

The vulnerability extends upstream to the very manufacturing of the chips themselves. Semiconductor fabrication is an inherently wet process. “Ultra Pure Water” (UPW)—water treated to be thousands of times purer than drinking water—is essential for rinsing silicon wafers during production. A single advanced fabrication plant can consume millions of gallons of water daily, creating a direct competition between national security assets and local agriculture.

This creates a collision course between the digital economy and climate reality. The locations currently favored for tech hubs, such as California’s Silicon Valley, the corridor between Phoenix and Texas, and parts of the Mediterranean, are facing chronic aridification. The industry has treated water as a cheap, infinite utility. In the coming decade, it will become a hard strategic cap on growth.

The United States provides the clearest example of this strategic dissonance. Under the auspices of the CHIPS and Science Act, Washington has successfully incentivized the construction of massive semiconductor foundries in the American Southwest. This policy solves a geopolitical problem regarding the vulnerability of Taiwan but replaces it with an environmental one. Placing the most water-intensive manufacturing processes in a region facing chronic aridification and reliance on the shrinking Colorado River introduces a point of failure that no amount of kinetic defense can mitigate.

This is the Arizona Paradox. By prioritizing distance from Chinese ballistic missiles, planners have ignored the constraints of the terrain. While companies like Intel have invested in advanced water reclamation systems to mitigate local scarcity, technology cannot manufacture rain. In a scenario of prolonged megadrought, federal authorities may be forced to choose between the cooling needs of a strategic asset and the hydration of the civilian population. Recent data indicates that the thermoelectric power sector, which supports these data centers, still withdraws trillions of gallons annually for cooling, linking the stability of the grid directly to river levels.

The Rise of Hydro-Hegemony

If water is a prerequisite for compute, then the balance of power must shift toward the wet and the cold. A new class of “Hydro-Hegemons” is likely to emerge. These are states possessing the dual endowments of abundant freshwater and cool ambient temperatures, which drastically reduce the energy required for data center cooling.

Nations such as Canada, Norway, and Finland are positioned to become the “Saudi Arabia of Compute.” These nations possess what experts call “free cooling” potential—ambient air temperatures low enough to cool servers without energy-intensive chillers for much of the year. Combined with abundant hydropower, they offer a lower total cost of ownership (TCO) and a lower carbon footprint. In 2025, drought conditions in Norway caused a distinct spike in energy prices, demonstrating how tightly energy, water, and economics are now wound. Yet these nations still possess a structural advantage over arid competitors.

This creates coercive leverage. In a digitized global economy, the state that hosts the servers holds the keys to the kingdom. These host nations could plausibly leverage their position to extract rents, impose data localization standards, or exert diplomatic pressure on the “user states” that rely on their infrastructure. Just as petrostates leveraged oil reserves in the twentieth century, hydro-states could leverage their thermal capacity. A country like Iceland or a province like Quebec becomes not just a passive host for server farms but a strategic node in the global information architecture.

The Sovereignty Trap

This hydrologic reality poses a severe challenge to the concept of “Sovereign AI.” Nations across the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and parts of Europe are currently rushing to build domestic AI infrastructure to avoid dependency on American or Chinese tech giants. However, sovereignty requires physical capacity.

Consider the Gulf states or Singapore. Both have capital and political will but lack natural freshwater abundance. Singapore has already had to impose moratoriums on new data centers due to energy and water constraints. While desalination is an option, it binds AI ambitions to energy-intensive water production, driving up costs and carbon footprints in a way that makes domestic hosting uncompetitive.

Eventually, simple physics may force these nations to “offshore” their training runs to water-rich jurisdictions, maintaining only the lighter “inference” infrastructure at home. This creates a new form of dependency. A nation that must export its data to be processed in a foreign jurisdiction because it lacks the water to cool the processors at home is not fully sovereign. It is reliant on the environmental goodwill of the host nation. We may see a bifurcation of the digital world: “Training Hubs” located in the wet, cold north, and “User Hubs” in the populous, warmer south.

Asian Ambitions and the Himalayan Constraint

The water constraint is particularly acute in Asia, the center of global semiconductor manufacturing. A recent report by Planet Tracker warned that the majority of existing data centers in Asia are located in areas of high water stress, including key hubs in China and India.

China faces a particularly severe hydrologic bottleneck. While it is aggressively building out renewable energy capacity, adding 429 GW of new power generation in 2024 alone, its water resources are unevenly distributed. The South-North Water Transfer Project highlights the desperate measures Beijing must undertake to hydrate its industrial north, where much of its technological apparatus is concentrated. The ability of Beijing to sustain exponential growth in compute will be capped by the availability of water in the Yellow River basin. In a direct conflict, this centralization creates a fragility; a disruption to water infrastructure is now a disruption to intelligence capabilities.

A Realist Hydro-Strategy

For the United States, the integration of water security into high-tech industrial policy is no longer an environmental luxury. It is a strategic imperative.

First, industrial planning must align with hydrologic data, meaning policymakers should consider local water availability and long-term climate conditions when deciding where to build critical technology infrastructure. Incentives for data centers and semiconductor fabs should be tied to watershed resilience, or the ability of nearby rivers, reservoirs, and groundwater systems to reliably supply water over time. It makes little strategic sense to protect a supply chain from foreign military threats if that same infrastructure is vulnerable to water shortages caused by drought. The Department of Commerce should mandate “Water Usage Effectiveness” (WUE) reporting for all CHIPS Act recipients, treating water efficiency as a national security metric.

Second, the United States should leverage the natural endowments of its alliance network. NATO includes some of the most water-secure nations on the planet. Integrating digital infrastructure planning into alliance commitments could create a “computing bloc” that offers a level of physical resilience that rivals cannot replicate. Rather than competing with Canada or the Nordics for data center investment, the US should view them as strategic depth—secure, resource-rich reservoirs for the West’s collective intelligence.

The era of treating the digital cloud as ethereal is over. The cloud is physical. It is made of steel, silicon, and vast amounts of water. As the demand for synthetic intelligence grows, the most enduring advantage will belong to the nations that can quench the thirst of the machines.

Image credits: Hanwha Data Centers

Xiaolong (James) Wang

James is a Master of Science in Foreign Service student at Georgetown University specializing in AI and digital governance. Born in China and raised in Singapore, he completed his bachelor degree in Canada. James has worked with the G20 Research Group and the NATO Association of Canada, focusing on global governance, security policy, and multilateral diplomacy.