Mark Carney’s landmark trade agreement with China—reducing Canadian EV tariffs to 6.1% in exchange for slashed canola tariffs—proves that Canada’s long-failed quest for strategic autonomy can succeed. But only when built on power, not ideology: Carney is fixing Pierre Trudeau’s Third Option by securing material strength first, then diversifying from that foundation.

In 1969, Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau launched what he called the “Third Option.” His vision was bold: Canada would reduce its dependence on the United States through diversified trade relationships and independent foreign policy. It was intellectually serious, rooted in legitimate concern about American dominance. By the early 1980s, it had failed spectacularly. U.S. trade dependence actually increased from 67.9 percent to 78.8 percent. American direct investment tripled from $22 billion to $66 billion. Trudeau’s nationalist policies did not slow the tide of continental integration.

Fifty years later, Prime Minister Mark Carney is reviving that vision. But this time, he has learned a crucial lesson from Trudeau’s failure: you cannot achieve strategic autonomy through rhetoric alone. You must build material strength first. Then you can credibly diversify.

The evidence arrived in Beijing earlier last month. Carney returned from his first visit to China as prime minister with a landmark trade agreement that proves his approach works where Trudeau’s rhetoric failed. Canada reduced its tariff on Chinese electric vehicles from 100 percent to 6.1 percent. In exchange, China reduced its canola tariffs from 84 percent to approximately 15 percent by March 1, 2026. The Canadian government expects nearly $3 billion in new agricultural exports. Chinese manufacturers are expected to begin assembling EVs and components in Canada within three years.

This is not Trudeau’s failed diversification strategy. This is pragmatic engagement from a position of strength.

Trudeau’s core problem was structural. He attempted to achieve diversification without first building the economic and military capacity to withstand American pressure. He created the Canada Development Corporation to keep key industries in Canadian hands. He established the Foreign Investment Review Agency to screen foreign takeovers. He launched Petro-Canada as a state-owned oil company. He pursued a European framework agreement. These were serious initiatives. But they rested on a faulty foundation. Canada remained vulnerable to U.S. economic coercion precisely because it lacked the material capacity to withstand it.

The OPEC shocks of 1973 and 1979 exposed this vulnerability. The oil price collapse of 1982 devastated the federal government’s revenue projections. Petro-Canada’s expansion, which was supposed to build Canadian energy sovereignty, became economically unviable. Trudeau’s nationalist agenda could not survive the intersection of commodity volatility and structural economic dependence. By the 1980s, U.S. trade dependency had actually deepened despite his policies. Political will had dissipated. The Committee for an Independent Canada, which had championed Trudeau’s vision, dissolved in 1981.

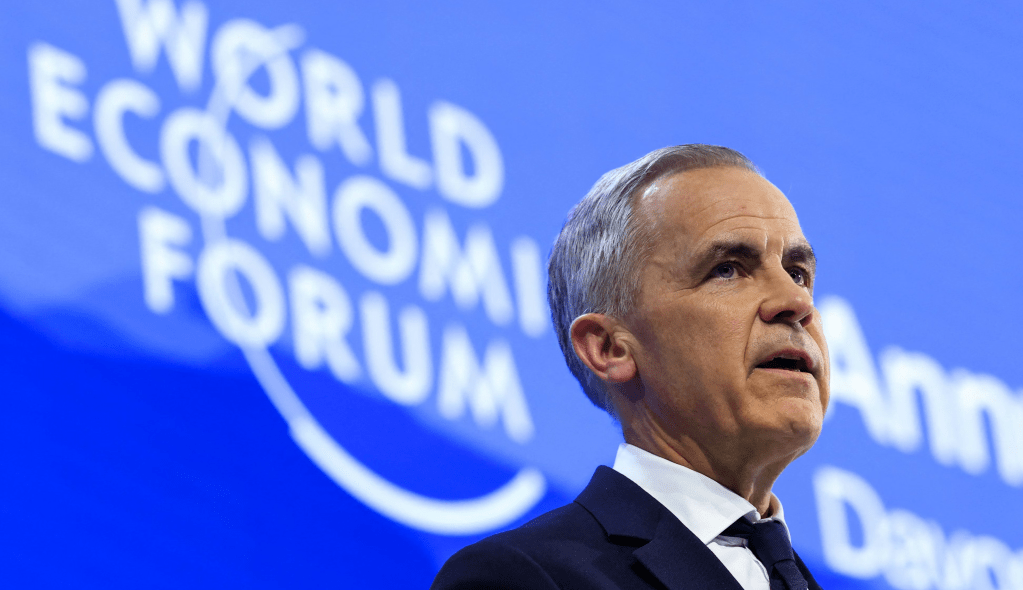

Carney diagnosed this failure and prescribed a different remedy. At the World Economic Forum in Davos on January 20, Carney delivered a provocative address to world leaders. The rules-based international order, he argued, is effectively dead. Great powers no longer follow the rules. Instead, they weaponize economic integration, financial systems, and supply chains to coerce rivals. Middle powers face a choice: negotiate bilaterally with hegemons from weakness and accept subordination, or band together to build something new. “If you are not at the table,” Carney told the assembled delegates, “you are on the menu.”

His diagnosis was unflinching. The old world order “is not coming back.” But he offered something Trudeau never could: not nostalgia for a rules-based system that no longer functions, but a pragmatic path forward. Middle powers can build coalitions based on shared interests. They can pursue what Carney calls “values-based realism.” They can reduce their vulnerability to coercion by building strength at home: energy independence, critical minerals dominance, AI leadership, defense spending doubled by 2030. Only from that material foundation can they credibly diversify and act independently.

Since taking office in March 2025, Carney has been executing this vision. The Beijing deal is the first concrete evidence that this approach produces results. It is the living proof of what Carney outlined in Davos one week earlier.

Canada negotiated from strength rather than weakness. Canada has something China wants: energy resources, critical minerals (23 percent of global lithium reserves), and political stability. In exchange, Canada gains market access and manufacturing investment. Both sides benefit. Neither is subordinate. This is Carney’s “values-based realism” in practice.

Most importantly, Carney’s pragmatic engagement with China removes a critical constraint on Canadian foreign policy: fear of Chinese economic retaliation.

For fifty years, Canada has been economically engaged in Southeast Asia but strategically peripheral. Canada committed over $2.8 billion in development assistance to the region since becoming an ASEAN Dialogue Partner in 1977. Yet Canada has zero defense partnerships with ASEAN states. Canada remains silent on the South China Sea disputes, the region’s most pressing security challenge. This silence does not flow from principle or multilateral restraint. It flows from fear. China is Canada’s second-largest trading partner. Any explicit advocacy for freedom of navigation or rules-based maritime order risks antagonizing Beijing and jeopardizing market access.

Carney’s Beijing deal changes this calculation fundamentally. By securing a pragmatic partnership with China on energy and trade, Canada reduces its vulnerability to Chinese economic coercion. This creates space for honest diplomacy in Southeast Asia, the kind Carney called for in Davos.

Imagine what this enables. Canada could now co-lead a South China Sea transparency initiative alongside Vietnam, the Philippines, and Indonesia. It could fund expanded trilateral maritime patrols with Indonesia and the Philippines, which have proven effective at addressing regional piracy and security challenges. Canada could participate in semiconductor supply chain resilience coalitions with Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, ensuring production capacity exists outside Beijing’s control. It could set AI governance standards alongside India, Australia, and South Korea, the democracies most concerned about authoritarian control of artificial intelligence.

These are the “variable geometry” coalitions Carney discussed in Davos: different groupings for different issues, each assembled based on shared interests rather than rigid alliance structures. They operate outside ASEAN’s consensus machinery, which privileges caution and non-interference. They respond to actual security problems at the speed those problems demand.

None of this was possible when Canada was hostage to fear of China economic retaliation. Carney’s pragmatism has broken that hostage situation.

The geopolitical window for middle power action in Southeast Asia is narrow. Trump’s protectionism creates space for Canadian independence from American strategic dictation. But China is simultaneously consolidating economic dominance throughout the region. ASEAN states are actively seeking alternatives to bilateral great power engagement. Japan, Australia, and South Korea are already moving on minilateral arrangements. If Canada delays, other middle powers will claim coalition leadership.

Carney has announced concrete material commitments to match this ambition. A $1 trillion domestic investment program in energy, artificial intelligence, critical minerals, and trade corridors. Defense spending will double by 2030. These are not rhetorical promises. These are fiscal commitments that require approval and execution.

The real test comes now. In Davos, Carney told the world that the old order is finished and middle powers must act. In Beijing, he showed what that action looks like. The question is whether he will translate this vision and pragmatism into sustained Southeast Asian engagement.

Will Canada establish defense partnerships with ASEAN states proportional to its stated Indo-Pacific ambitions? Will it co-lead minilateral coalitions on maritime security, supply chain resilience, and AI governance? Will it match defense investment to strategic presence, rather than maintaining symbolic dialogue forums? Will it extract itself from the fear-based passivity that has defined Canadian policy toward the region for fifty years?

Trudeau was right in principle. Canada should not accept strategic subordination to the United States or any other power. But he was wrong in execution. He believed diversification could be achieved through nationalist ideology without material foundation. Carney has diagnosed that error.

The irony is profound: Trudeau’s anti-nationalist intellectual instinct prevented him from building the domestic strength that genuine nationalism requires. Carney’s pragmatism, unconstrained by that ideological aversion, might finally achieve what Trudeau could only dream of.

But dreams and reality remain distinct. Davos was the vision. Beijing was the proof. Southeast Asia will be the test.

Image credits: Heute.at

Xiaolong (James) Wang

James is a Master of Science in Foreign Service student at Georgetown University specializing in AI and digital governance. Born in China and raised in Singapore, he completed his bachelor degree in Canada. James has worked with the G20 Research Group and the NATO Association of Canada, focusing on global governance, security policy, and multilateral diplomacy.