China-Southeast Asia relations is best defined in terms of the plurality of interests, incentives and capabilities characteristic of the diverse states that make up the region. It is perhaps not the most useful, therefore, to refer to a “China-Southeast Asia relationship,” since such a label lacks nuance and conveys the idea of a homogenous Southeast Asia. The truth is that engagement between China and Southeast Asian states vary in complex, diverse ways, depending on particular political, cultural and economic constraints specific to each country. Within each state, varying ideological leanings across the populace imply groups in society who are more or less receptive to China. Varying national interests and incentives imply oscillations in a state’s ability to engage China. Simply put, sentiment towards Beijing diverge within and across state lines.

In 2025, where do China-Southeast Asia relations stand? Recent headlines display episodes of bilateral engagement in trade and investment which stand in stark contrast to geopolitical disputes in the South China Sea. A newly-elected Trump 2.0 administration more hawkish than its predecessor and more willing to apply tariffs on China imply uncertainty about the fate of Southeast Asia, which uniquely stands at the critical crossroads of protectionist measures against China. China-Southeast Asia relations are complex and multidimensional. Most central are the economic, geopolitical and ideological dimensions. Each of these dimensions represents opportunities and constraints in the way engagement with China takes place. In 2025, China-Southeast Asia relations will ultimately be defined in terms of these opportunities and constraints.

A question of economic integration?

China is and has been ASEAN’s largest trading partner since 2009. In 2020, ASEAN became China’s largest trading partner, surpassing the European Union such that today, China and ASEAN are each other’s top trading partner. The region figures prominently in China’s flagship international development project, the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The BRI’s China-Indochina Peninsula economic corridor (CICPEC) epitomizes the push for regional economic integration, and will cross Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar and Malaysia. Evidently, central to China-Southeast Asia relations is economic integration. In 2020, ASEAN became the world’s fifth largest economy. Both regions, then, as the second and fifth largest economies in the world, stand to derive immense gain from economic cooperation and trade, especially as an emerging Southeast Asia is set to be one of the fastest growing regions globally.

Perhaps here one ought to take a step back to see how China and Southeast Asian states have steadily integrated themselves economically. In 2010, the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) was signed. Then, signed in 2022, The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) established the largest FTA in the world. Today, China is further seeking to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), although issues regarding Taiwan are ostensibly impeding the process.

The United States, in comparison, is only ASEAN’s fourth largest trading partner. That said, the US provides the most foreign direct investment into Southeast Asia. Chinese investment, instead, lags behind the US, Japan and the European Union. Further, while it is true that China is ASEAN’s bilateral trading partner, ASEAN runs a sizable trade deficit with China. Chinese overcapacity of goods like electric vehicles could have negative employment consequences for ASEAN economies. Chinese export gluts, if persistent in 2025, could complicate the wider trade relationship between Southeast Asian states and China that has thus far proven to be overwhelmingly positive. Importantly, Southeast Asia has a track record of not wanting to choose sides in the wider US-China rivalry. A Trump 2.0 administration willing to deepen economic cooperation with the region would be welcomed, especially as economic overreliance on China may compromise a states’ ability to negotiate over other political or security issues. As US-China relations scholar David Lampton writes:

“Neither Washington nor Beijing is inclined to be accommodating towards the other in Southeast Asia. Consequently, Southeast Asian nations must seek ways to gain from the big-power competition on the one hand while not getting caught in the gears of the contest on the other.”

The geopolitical reality

Southeast Asia is of utmost geopolitical and strategic importance to China. On one hand, Southeast Asia is vital to China’s security interest, since much of the crude oil China uses is shipped through the Strait of Malacca and South China Sea. More fundamentally, Southeast Asia’s economic, geostrategic and diplomatic influence via ASEAN makes it a region of strategic significance to both big powers. The search for reliable allies in the region is thus a critical feature in the US-China rivalry.

To China, Southeast Asia represents a large bloc of geographically proximate potential allies in a region that has seen increasing US involvement. The US and regional allies including Japan, South Korea and Australia regularly commit to strengthening military cooperation. The US has often stood with Southeast Asian allies in defence of freedom of the seas and rejected China’s South China Sea claims. AUKUS, a trilateral security pact between the US, UK and Australia, seeks to equip Australia with nuclear-powered submarines. China has pushed back, stating that the actions “incite bloc politics” and “hurt regional peace and stability.” For China, US actions in the region represent provocations in its own backyard and undermine its authority as a regional power. Given the US’ robust military cooperation with allies in the region, which also includes Vietnam and Taiwan, it is easy to see how China may view the US’ presence as “encirclement.”

At the same time, China has, over the years, expanded both its capacity and willingness to deploy hard power in service of its regional security ambitions. Consider the disputes in the South China Sea, where China’s maritime claims span an expansive area according to the nine-dash line. The Philippines launched a two-and-a-half-year lawsuit over China’s claims at the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague. While the Court ultimately ruled in favor of the Philippines in 2016, China dismissed the ruling and retaliated by placing a ban on Philippine banana exports. When the Philippines temporarily stopped its efforts to enforce Hague’s decision, Beijing lifted the ban on bananas and indicated willingness to increase imports of a range of goods. This so-called “banana diplomacy” can be seen to represent China’s ability to use economic pressure to influence states with which China has geopolitical disputes.

Consider further the case of Cambodia. For Cambodia, an effectively single-party state with a poor human rights track record, access to Western financing is difficult, making China a critical provider of economic support. In turn, Cambodia is one of China’s strongest political allies on the international stage. Cambodia shares a near-identical UNGA voting record with China. Unsurprisingly, Cambodia is accused of pursuing a strategy of “bandwagoning towards China to accrue economic interests.” In 2016, ASEAN struggled to reach a consensus on maritime disputes after Cambodia sided with Beijing against The Hague’s ruling in favor of the Philippines.

It is difficult to imagine how such territorial deadlocks are to be resolved without extensive negotiation and compromise. As was the case with Trump 1.0, while a Trump 2.0 administration may entail greater US presence and maritime operations in the South China Sea, such geopolitical disputes are likely to persist into the foreseeable future, as Southeast Asian states continue to thread carefully between pursuing their geopolitical security interests and accommodating China.

What about ideology?

Southeast Asia is often characterized by a plurality of ethnicities and cultures, both within and across countries. Consider the country of Malaysia. Malaysia’s multiculturalism often sits at the heart of its national identity, with sizeable fractions of Malay, Chinese, Indian and indigenous peoples partaking in varied linguistic, religious and cultural practices.

In states like Malaysia and Indonesia, Muslim populations bear stronger anti-Western sentiment owing to factors like Islamophobia associated with global war on terror. The US’ long-standing support for Israel, recently most evident through arms sales to Israel in the aftermath of the October 7th Hamas attack, further entrenches such sentiment. In contrast, Beijing has broadly condemned Israel’s response and refused to condemn Hamas. A survey by the ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute found that from 2023 to 2024, both Malaysia and Indonesia saw a large spike in the percentage of respondents who believe ASEAN should align itself with China instead of the US (Fig. 1).

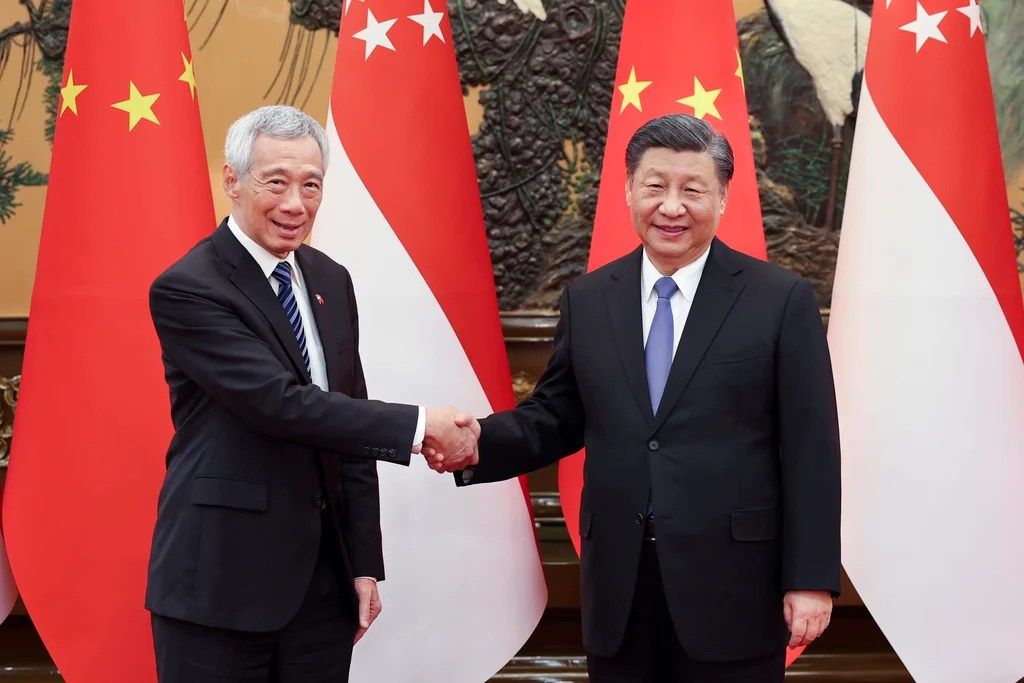

At the same time, Southeast Asia hosts a substantial share of the global Chinese diaspora—Southeast Asian Chinese account for about 80% of the 50 million ethnic Chinese overseas. Such overseas Chinese, who may possess a greater tendency to support China over other actors vying for influence such as the US, represent an important demographic through which China can advance its strategic interests. Beijing recognizes this. In 2022, Chinese President Xi Jinping stressed the important role “Chinese sons and daughters at home and abroad” play in “uniting all Chinese people to achieve the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.”

Across the economic, geopolitical and ideological dimensions, each Southeast Asian state navigates its own unique package of accords and disputes with China. Communist Party-run Vietnam may maintain direct party-to-party ties with China, cooperating on matters of ideology and internal security. Simultaneously, it maintains harder-line stances over matters of national security, such as in its maritime disputes with China in the South China Sea. Striking a balance between accommodating China and addressing domestic pressures is a key aspect of a state’s decision-making process. In May 2014, anti-China riots saw thousands of Vietnamese set fire to foreign factories as a reaction to Chinese oil drilling in the South China Sea. Sentiment towards China in Vietnam and the Philippines is seen to have deteriorated in 2024 (Fig. 1), a likely reflection of growing frustration both states bear towards China’s obstinacy over disputes in the South China Sea.

In 2025, what can we expect for China-Southeast Asia relations? Many questions and uncertainties remain. Will Trump impose tariffs or export controls on China? How will China’s economy fare amid a housing market meltdown and deflationary pressures? Is a stimulus package forthcoming? Such questions are crucial for a region deeply intertwined with regional supply chains and already grappling with a persistent trade deficit with China. At the end of the day, Southeast Asian states, wary to prevent being caught in the crossfires of the US-China rivalry, have and will continue to position themselves to benefit from the presence of both big powers. Thus, while Malaysia seeks to attract Chinese investments, it also continues to strengthen military cooperation with the US. Caught between a rock and a hard place, Southeast Asian states realize they perhaps ought not to choose sides. Both major powers present themselves ultimately as strategic counterweights to each other in a region committed to preserving its own agency.

Image credits: Xinhua/AP