The strategic partnership between the United States and ASEAN has never fully recovered from the shock of the Trump administration’s 2016 turn away from multilateralism, erratic diplomacy, and rising protectionism. Years of unpredictable US policy have eroded trust, leaving ASEAN leaders doubtful about Washington’s long-term reliability. Into this vacuum steps China, wielding the newly finalized ACFTA 3.0 to tighten its economic grip on Southeast Asia. The October 2024 update touts reforms on digital trade and green growth, but fundamentally deepens China’s hold over regional infrastructure, markets, and political leverage. Over 100 days into Trump’s second term and his tariffs, the question for ASEAN is no longer whether dependency on China is growing—it is whether the region can still shape the terms of that dependency before it becomes irreversible.

The ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA), established in 2002, was once heralded as a landmark agreement that would usher in an era of mutual prosperity. It was meant to reflect a new economic reality in which China and its Southeast Asian neighbors would develop together, breaking down trade barriers and fostering deeper regional integration. And in many ways, ACFTA has delivered. Trade between ASEAN and China has ballooned, surpassing $911.7 billion in 2023. China has become ASEAN’s largest trading partner, a position it has held for over a decade. But beneath the headline figures of record-breaking trade volumes lies a more complicated reality: one that increasingly raises questions about whether ACFTA has been a balanced and fair partnership, or if it has primarily served as a vehicle for Beijing’s economic ambitions at the expense of ASEAN’s long-term development.

At the core of the debate is the asymmetry of benefits. China, with its vast manufacturing base and state-backed industrial policy, has used ACFTA to flood ASEAN markets with cheap exports, from steel and textiles to consumer electronics. This influx has often come at the expense of local industries in ASEAN states, many of which struggle to compete with Chinese firms that enjoy economies of scale and, in many cases, significant government subsidies. The result has been a widening trade imbalance, with ASEAN countries importing far more from China than they export. While some economies, particularly Vietnam, Malaysia, and Singapore, have capitalized on ACFTA by integrating into China’s supply chains, others, such as Indonesia and the Philippines, have seen entire sectors of their economy undermined by Chinese competition.

Yet, trade asymmetry alone does not fully capture the challenges that ACFTA presents. The agreement has also reinforced ASEAN’s economic dependency on China, a reality that became glaringly evident during the COVID-19 pandemic. As global supply chains fractured, ASEAN economies found themselves heavily reliant on Chinese production networks for essential goods, from pharmaceuticals to raw materials. This reliance extends beyond goods trade to foreign direct investment (FDI), where China’s expanding presence in Southeast Asia has raised concerns over sovereignty and long-term economic autonomy. Chinese companies have poured billions into infrastructure, real estate, and technology sectors across ASEAN, but these investments often come with strategic strings attached. In Laos and Cambodia, Chinese-backed projects have led to debt dependency, with Beijing gaining control over critical infrastructure projects in exchange for financial assistance.

Recent developments have only added to the urgency of reassessing ACFTA’s role. The completion of ACFTA 3.0 in October 2024 introduces new provisions focused on digital trade, the green economy, and supply chain resilience—seemingly in response to the mounting criticisms of the agreement’s earlier phases. But will these reforms address the fundamental imbalances that have characterized ASEAN-China trade relations for the past two decades? Or are they merely cosmetic adjustments that will allow Beijing to maintain its economic leverage over the region?

The Early Years (2001–2010): The Push for Regional Integration

When ASEAN and China first embarked on the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA), the agreement was marketed as a turning point in regional economic integration, a move that would propel ASEAN onto the world stage as a united economic bloc and deepen its connectivity with the world’s fastest-growing economy. At the time, China was in the early phases of its meteoric rise following its 2001 accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), and ASEAN nations were eager to position themselves as beneficiaries of China’s expanding markets and insatiable demand for raw materials, agricultural goods, and industrial components. From its inception, however, ACFTA was more than just a trade pact—it was an economic and political instrument, one that reflected both Beijing’s long-term ambitions for regional dominance and ASEAN’s persistent balancing act between economic opportunity and strategic autonomy.

The signing of the Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Cooperation between ASEAN and China in November 2002 set the stage for the gradual elimination of tariffs on nearly 90 percent of goods traded between the two sides. The agreement was formally implemented in 2010, creating what was at the time the largest free trade area in the world by population, covering 1.9 billion people. Tariff reductions were implemented in two phases: first for the six more developed ASEAN economies—Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand—and later for the remaining four less developed members—Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam.

These early years saw explosive growth in trade volume. ASEAN exports to China surged, particularly in raw materials, agricultural products, and energy resources, feeding into China’s booming industrial machine. Meanwhile, Chinese goods, notably machinery, textiles, steel, and electronics, flowed into ASEAN markets, reshaping local industries and consumer markets. The numbers were staggering: between 2003 and 2013, total trade between China and ASEAN grew from $59.6 billion to over $400 billion, a nearly sevenfold increase.

For China, ACFTA offered strategic economic advantages. By securing preferential access to ASEAN’s markets, Beijing strengthened its role as the dominant manufacturing hub in the region. Chinese companies flooded ASEAN with low-cost goods, benefiting from production advantages that local firms could not match. At the same time, China secured stable access to key raw materials, ensuring uninterrupted inputs for its industrial supply chains, particularly for sectors like steel, coal, and palm oil.

ASEAN countries, meanwhile, found themselves in a mixed economic position. Nations like Malaysia, Vietnam, and Thailand, which successfully integrated into China’s supply chains, reaped significant benefits from increased exports of electronics and components. However, countries like Indonesia and the Philippines, whose domestic industries faced overwhelming competition from Chinese imports, experienced economic strains in key sectors such as textiles, steel, and agriculture. By the end of the decade, concerns over economic asymmetry were already beginning to surface.

The Trade Imbalance Becomes Apparent (2011–2019): China’s Growing Dominance

As ACFTA entered full implementation, the early optimism surrounding the agreement began to fade in certain ASEAN quarters. While trade volumes continued to rise, the balance of benefits was increasingly skewed toward China. By 2019, China-ASEAN trade had reached $644 billion, but ASEAN’s trade deficit with China had widened dramatically, with imports far outpacing exports in many countries.

This period also saw China’s growing involvement in ASEAN’s infrastructure and investment landscape, facilitated by the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013. The BRI and ACFTA increasingly became intertwined, as Chinese capital flooded ASEAN through investments in roads, ports, energy projects, and industrial zones. While these projects contributed to economic growth, they also raised alarms over debt dependency. Countries like Laos and Cambodia became heavily reliant on Chinese loans, raising concerns over Beijing’s long-term strategic influence in the region.

At the same time, ACFTA exacerbated structural weaknesses within ASEAN economies. While some nations continued to benefit—Vietnam, for instance, leveraged the agreement to become a major player in China’s manufacturing ecosystem—others saw their domestic industries eroded by cheap Chinese imports. The flood of low-cost Chinese steel into ASEAN sparked particular controversy, with local producers in Indonesia and Malaysia suffering heavy losses, while automobile and electronics manufacturers across the region struggled to compete with China’s heavily subsidized industrial giants.

The growing perception that ACFTA disproportionately benefited China led to mounting criticism within ASEAN. Many governments began exploring trade diversification strategies, signing bilateral trade agreements with the European Union, expanding ties with Japan and South Korea, and joining regional pacts like the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). While ASEAN leaders continued to emphasize the importance of economic cooperation with China, there was a growing sense that the original ACFTA framework needed an overhaul.

The Push for ACFTA 3.0 (2020–2024): Recalibration in an Era of De-Risking

The outbreak of COVID-19 in 2020 exposed the fragility of ASEAN’s trade dependence on China. Supply chain disruptions, factory shutdowns, and a slowdown in Chinese demand had immediate ripple effects across ASEAN economies. Countries that had become too dependent on Chinese markets—such as Malaysia, Thailand, and Indonesia—found themselves struggling to adjust to global shifts in production and consumption patterns.

Amid these disruptions, the global trade landscape was shifting. The U.S.-China trade war, rising protectionism, and global calls for “de-risking” supply chains put renewed focus on ASEAN’s economic relationship with China. In response, negotiations for ACFTA 3.0 began, culminating in the agreement’s official conclusion in October 2024.

The ACFTA 3.0 upgrade seeks to address some of the challenges that have plagued the agreement over the past two decades. New provisions focus on digital trade, green economy initiatives, and trade facilitation aimed at reducing ASEAN’s trade dependency on Chinese manufacturing. There is also an increased emphasis on investment transparency and market access, particularly for ASEAN businesses seeking to expand into China.

However, skepticism remains. Many ASEAN policymakers worry that the new framework does little to address the structural trade imbalances that have long defined ACFTA. While digital trade and sustainability provisions are welcome, they do not fundamentally alter the competitive disadvantages faced by many ASEAN industries. More critically, the agreement does not address the concerns over Chinese industrial overcapacity, which continues to flood ASEAN markets with cheap steel, electronics, and manufactured goods.

ASEAN’s Growth Through ACFTA: The Winners

For some ASEAN states, ACFTA has been nothing short of transformative. Vietnam, Malaysia, and Thailand have been among the biggest beneficiaries, successfully integrating into China-centric supply chains. Vietnam, in particular, has emerged as a major manufacturing hub for electronics, textiles, and components, attracting billions in foreign direct investment from Chinese firms relocating operations to mitigate U.S. tariffs in the ongoing trade war. Vietnam’s exports to China have soared in electronics, machinery, and agricultural products, helping the country achieve some of the highest GDP growth rates in Southeast Asia over the past decade.

Malaysia, too, has leveraged its position as a high-tech manufacturing hub, particularly in semiconductors and integrated circuits, where its role in China’s supply chain has deepened despite U.S. efforts to curtail Chinese access to advanced technology. The palm oil industry in Malaysia and Indonesia has thrived under ACFTA, with China serving as a massive consumer market, absorbing vast quantities of raw materials essential to its food and energy security.

Even Thailand, which has faced stiffer competition in certain industries, has benefited from rising agricultural exports and tourism revenue linked to growing Chinese middle-class consumption. The rise of Chinese tourism, investment, and manufacturing partnerships has helped Thailand maintain strong economic ties with China, even as the broader balance of trade has remained skewed in Beijing’s favor.

These ASEAN economies have played the ACFTA game well—adapting their industries, attracting Chinese capital and trade, and integrating into China’s industrial ecosystem. But success has come with strings attached. The deeper a country integrates into China’s economy, the harder it becomes to diversify trade relationships elsewhere, leaving many ASEAN nations caught in an increasingly China-dependent cycle.

The Losers: Industry Erosion and Trade Asymmetry

If some ASEAN nations have thrived under ACFTA, others have seen sectors of their economies weakened by the sheer force of Chinese competition. The most prominent casualties have been domestic manufacturing industries in Indonesia, the Philippines, and parts of Thailand, where local producers have struggled to compete with cheap Chinese imports in steel, textiles, and electronics.

Indonesia, despite being the region’s largest economy, has suffered heavily from China’s steel overproduction, with local mills unable to compete with the influx of subsidized Chinese steel that has flooded the market. The Indonesian government has repeatedly raised concerns over ACFTA’s trade imbalance, arguing that the agreement has done more to undermine local manufacturing than boost exports to China.

The automobile industry in ASEAN has also struggled. Countries like Malaysia and Thailand, once poised to become major automotive manufacturing hubs, have seen growth stagnate in the face of Chinese state-backed automakers flooding the region with cheaper alternatives. Many ASEAN car manufacturers simply cannot compete with the economies of scale and government subsidies that support China’s automotive sector, leaving them at a severe disadvantage.

The Philippines has faced a different set of challenges under ACFTA. With a weaker industrial base compared to its ASEAN neighbors, the Philippines has found itself primarily a consumer rather than a producer within the ACFTA framework. Its trade deficit with China has continued to expand, with Chinese goods dominating the market in everything from appliances to construction materials. The Filipino government has sought to diversify trade through new agreements with the U.S. and the European Union, but China’s economic influence remains difficult to counterbalance.

China’s Trade Surplus and ASEAN’s Economic Dependence

Despite ASEAN’s growing exports to China, the reality remains that China’s trade surplus with ASEAN continues to widen. This is not an accident—it is the result of a deliberate economic strategy in which China leverages ACFTA to gain access to raw materials while simultaneously using its superior manufacturing capacity to dominate consumer markets in the region.

ASEAN’s reliance on China has become particularly evident in critical industries like electronics, machinery, and infrastructure materials. In 2021, over 50% of ASEAN’s imports in these sectors came from China, reinforcing a dependency cycle in which ASEAN economies supply raw materials to China, only to import finished goods at a higher cost. This structure mirrors the old colonial trade dynamics, where raw material exporters remain subordinate to industrial powerhouses.

As China’s exports to ASEAN continue to surge, governments across the region are facing mounting pressure from domestic industries to impose protective measures. The Indonesian government has raised tariffs on certain steel imports, while Malaysia and Vietnam have launched anti-dumping investigations into Chinese goods that are undercutting local manufacturers.

Yet, ASEAN’s options for protectionism are limited. The very nature of ACFTA restricts the ability of ASEAN countries to implement broad protectionist policies, meaning they are locked into a system where competing with China is not just difficult—it is nearly impossible.

Some ASEAN states have attempted to counterbalance China’s influence by diversifying trade agreements. The Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and bilateral free trade agreements with the European Union offer some alternatives, but the economic reality remains: China is too deeply entrenched in ASEAN’s supply chains to be replaced overnight.

The Digital and Green Economy Provisions of ACFTA 3.0

The recently concluded ACFTA 3.0 negotiations, finalized in October 2024, include new provisions aimed at addressing some of these imbalances. The digital trade agreement seeks to create a more level playing field for ASEAN companies operating in e-commerce and fintech, allowing them greater access to the Chinese market. However, concerns remain that Chinese tech giants like Alibaba and Tencent will continue to dominate, limiting ASEAN firms’ ability to compete on equal terms.

The green economy provisions in ACFTA 3.0 are another attempt to shift the balance. With China pledging increased investment in ASEAN’s renewable energy sector, the hope is that Southeast Asian nations can benefit from the global transition away from fossil fuels while attracting green technology investment from Beijing. However, ASEAN’s policy makers remain cautious—China’s track record in past infrastructure deals has left many skeptical of whether these new commitments will lead to genuine economic rebalancing.

After more than two decades, the ASEAN-China Free Trade Area (ACFTA) stands as both a testament to Southeast Asia’s economic transformation and a symbol of its growing dependence on China. Trade has surged, investment has flowed, and industries have expanded, yet the structural imbalances within the agreement have become impossible to ignore. While some ASEAN nations have leveraged ACFTA to integrate into global supply chains, others have struggled against China’s overwhelming manufacturing dominance, rising trade deficits, and the erosion of domestic industries. The expansion of ACFTA 3.0, with its digital and green economy provisions, suggests an attempt at modernization, but whether it meaningfully shifts the balance of power remains in question. The more China embeds itself in ASEAN’s economic fabric, the harder it becomes for the region to assert its autonomy and hedge against economic coercion.

Despite these challenges, there is no reversing ASEAN’s economic entanglement with China, only the potential to navigate it more strategically. The region’s leaders must pursue aggressive trade diversification, strengthening agreements like the CPTPP, RCEP, and bilateral deals with Western economies to counterbalance China’s economic weight. ACFTA will remain central to ASEAN’s economic future, but its long-term success will be measured not just by trade volumes, but by whether it allows ASEAN to flourish as an independent economic bloc, rather than a satellite of Beijing’s ambitions. The next chapter of ACFTA will not be written in tariffs and market access alone—it will be shaped by the political choices ASEAN makes to define its own economic destiny.

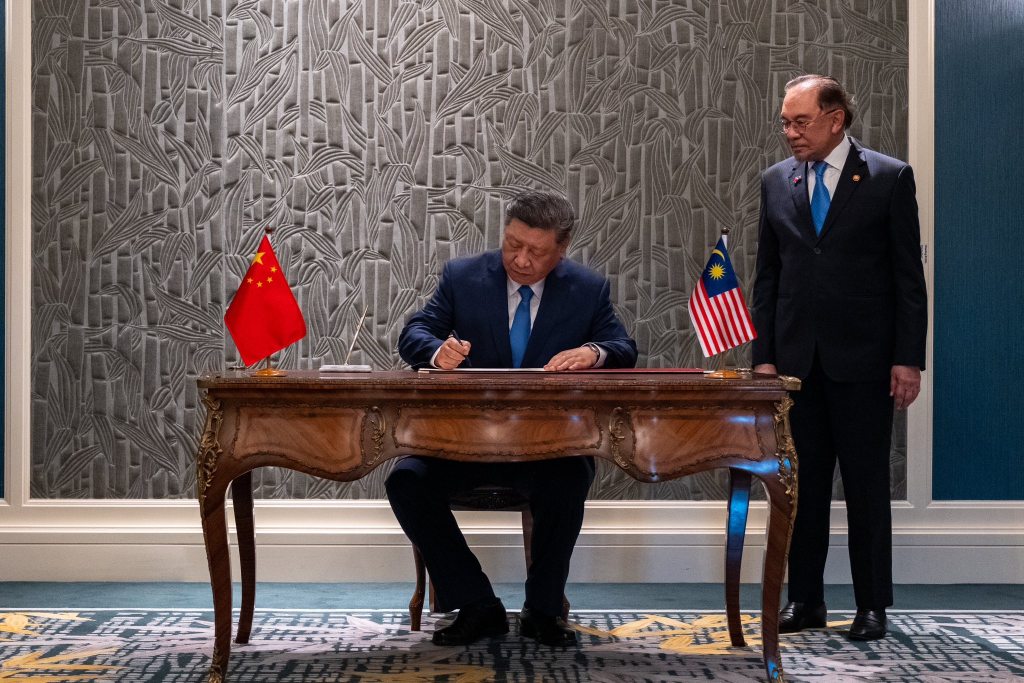

Image credits: Facebook page of Anwar Ibrahim.

James Wang

James is a researcher specializing in international relations and governance. Born in China and raised in Singapore, he is now based in Canada. James has worked with the G20 Research Group and the NATO Association of Canada, focusing on global governance, security policy, and multilateral diplomacy. James will start a master’s degree later this year.